Posted on January 16, 2015

In a

previous post, we explored techniques for visualizing high-dimensional data. Trying to visualize high dimensional data is, by itself, very interesting, but my real goal is something else. I think these techniques form a set of basic building blocks to try and understand machine learning, and specifically to understand the internal operations of deep neural networks.

Deep neural networks are an approach to machine learning that has revolutionized computer vision and speech recognition in the last few years, blowing the previous state of the art results out of the water. They’ve also brought promising results to many other areas, including language understanding and machine translation. Despite this, it remains challenging to understand what, exactly, these networks are doing.

I think that dimensionality reduction, thoughtfully applied, can give us a lot of traction on understanding neural networks.

Understanding neural networks is just scratching the surface, however, because understanding the network is fundamentally tied to understanding the data it operates on. The combination of neural networks and dimensionality reduction turns out to be a very interesting tool for visualizing high-dimensional data – a much more powerful tool than dimensionality reduction on its own.

As we dig into this, we’ll observe what I believe to be an important connection between neural networks, visualization, and user interface.

Neural Networks Transform SpaceNot all neural networks are hard to understand. In fact, low-dimensional neural networks – networks which have only two or three neurons in each layer – are quite easy to understand.

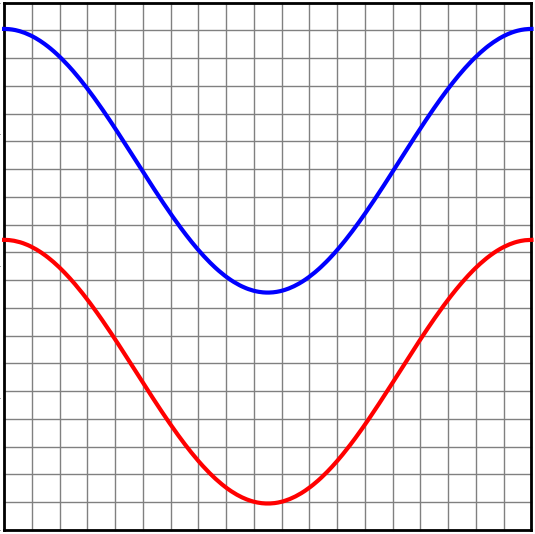

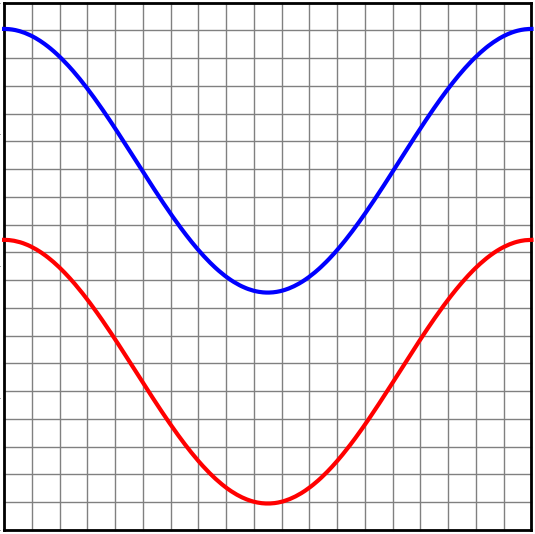

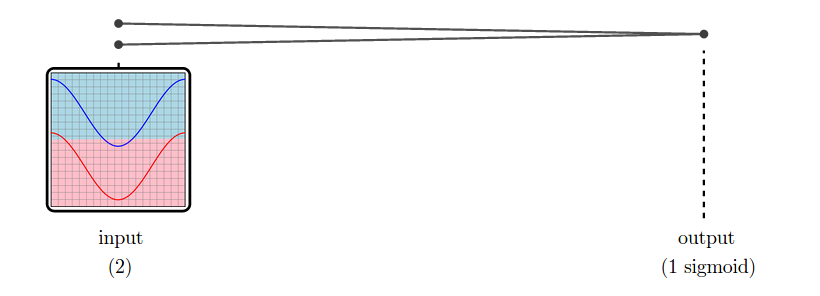

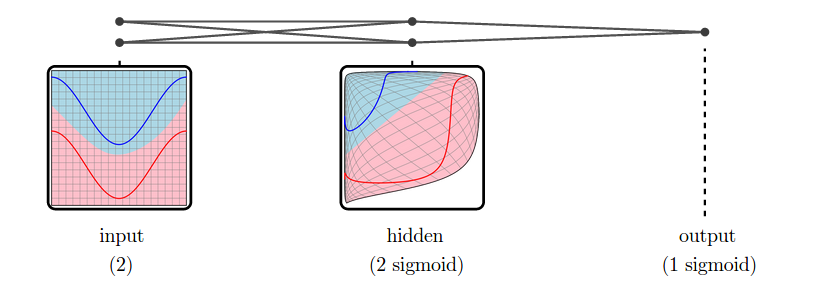

Consider the following dataset, consisting of two curves on the plane. Given a point on one of the curves, our network should predict which curve it came from.

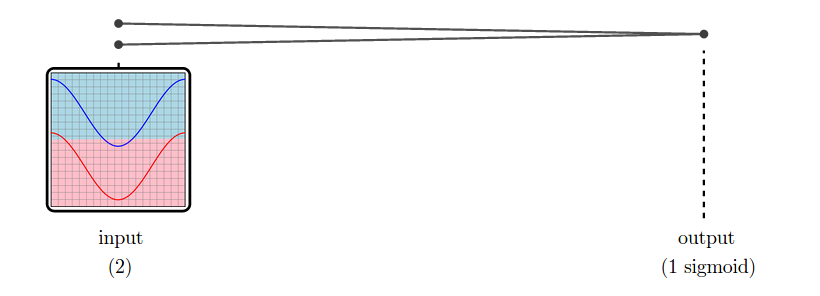

A network with just an input layer and an output layer tries to divide the two classes with a straight line.

In the case of this dataset, it is not possible to classify it perfectly by dividing it with a straight line. And so, a network with only an input layer and an output layer can not classify it perfectly.

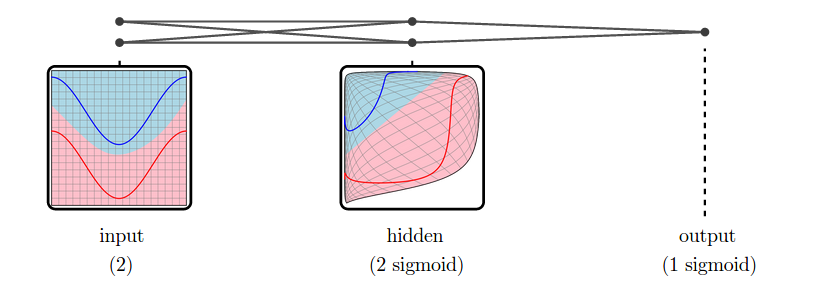

But, in practice, neural networks have additional layers in the middle, called “hidden” layers. These layers warp and reshape the data to make it easier to classify.

We call the versions of the data corresponding to different layers

representations.

1 The input layer’s representation is the raw data. The middle “hidden” layer’s representation is a warped, easier to classify, version of the raw data.

Low-dimensional neural networks are really easy to reason about because we can just look at their representations, and at how one representation transforms into another. If we have a question about what it is doing, we can just look. (There’s quite a bit we can learn from low-dimensional neural networks, as explored in my post

Neural Networks, Manifolds, and Topology.)

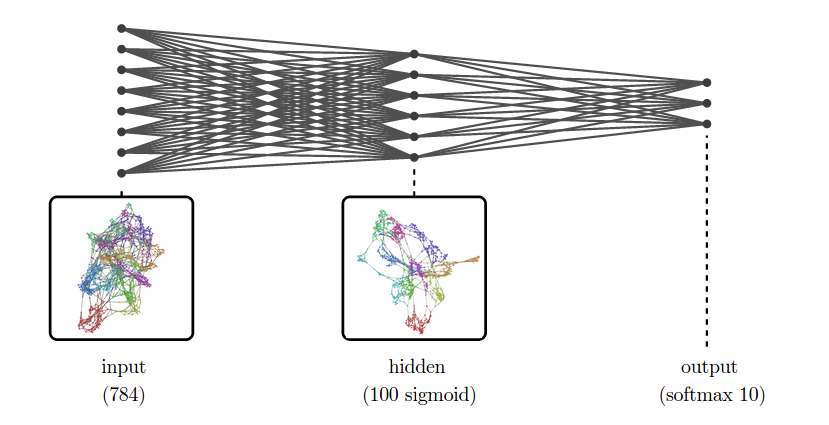

Unfortunately, neural networks are usually not low-dimensional. The strength of neural networks is classifying high-dimensional data, like computer vision data, which often has tens or hundreds of thousands of dimensions. The hidden representations we learn are also of very high dimensionality.

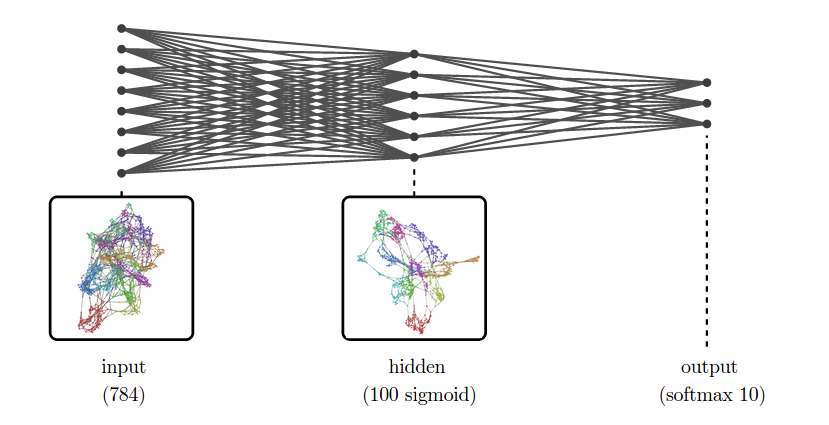

For example, suppose we are trying to classify MNIST. The input representation, MNIST, is a collection of 784-dimensional vectors! And, even for a very simple network, we’ll have a high-dimensional hidden representation. To be concrete, let’s use one hidden layer with a hundred sigmoid neurons.

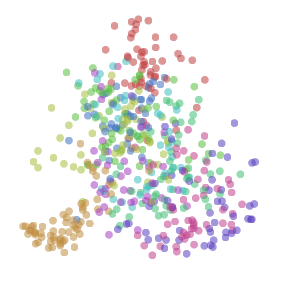

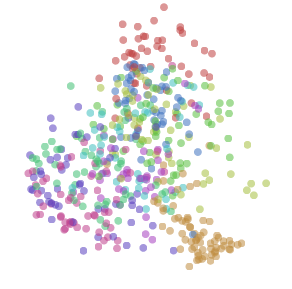

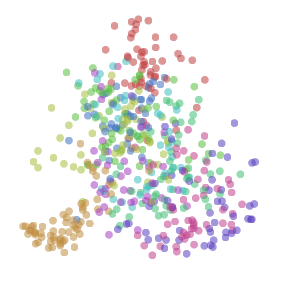

While we can’t visualize the high-dimensional representations directly, we can visualize them using dimensionality reduction. Below, we look at nearest neighbor graphs of MNIST in its raw form and in a hidden representation from a trained MNIST network.

At the input layer, the classes are quite tangled. But, by the next layer, because the model has been trained to distinguish the digit classes, the hidden layer has learned to transform the data into a new representation in which the digit classes are much more separated.

This approach, visualizing high-dimensional representations using dimensionality reduction, is an extremely broadly applicable technique for inspecting models in deep learning.

In addition to helping us understand what a neural network is doing, inspecting representations allows us to understand the data itself. Even with sophisticated dimensionality reduction techniques, lots of real world data is incomprehensible – its structure is too complicated and chaotic. But higher level representations tend to be simpler and calmer, and much easier for humans to understand.

(To be clear, using dimensionality reduction on representations isn’t novel. In fact, they’ve become fairly common. One really beautiful example is Andrej Karpathy’s

visualizations of a high-level ImageNet representation. My contribution here isn’t the basic idea, but taking it really seriously and seeing where it goes.)

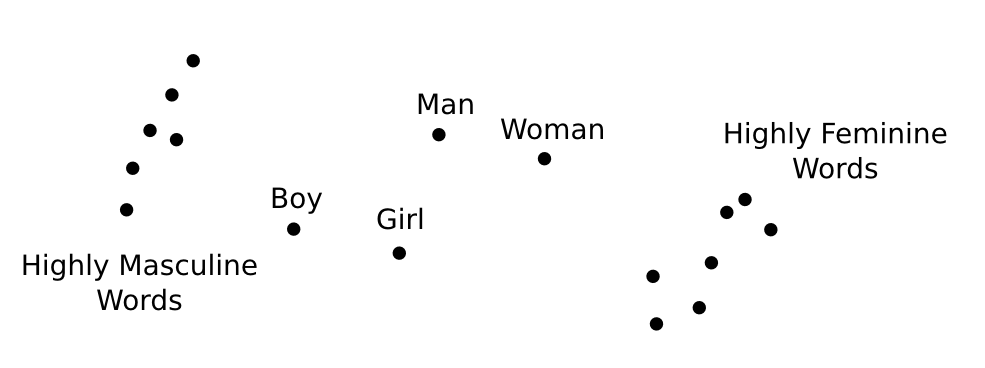

Word embeddings are a remarkable kind of representation. They form when we try to solve language tasks with neural networks.

For these tasks, the input to the network is typically a word, or multiple words. Each word can be thought of as a unit vector in a ridiculously high-dimensional space, with each dimension corresponding to a word in the vocabulary. The network warps and compresses this space, mapping words into a couple hundred dimensions. This is called a word embedding.

In a word embedding, every word is a couple hundred dimensional vector. These vectors have some really nice properties. The property we will visualize here is that words with similar meanings are close together.

(These embeddings have lots of other interesting properties, besides proximity. For example, directions in the embedding space seems to have semantic meaning. Further, difference vectors between words seem to encode analogies. For example, the difference between woman and man is approximately the same as the difference between queen and king: v(‘‘woman")−v(‘‘man") ≃ v(‘‘queen")−v(‘‘king"). For more on word embeddings, see my post

Deep Learning, NLP, and Representations.)

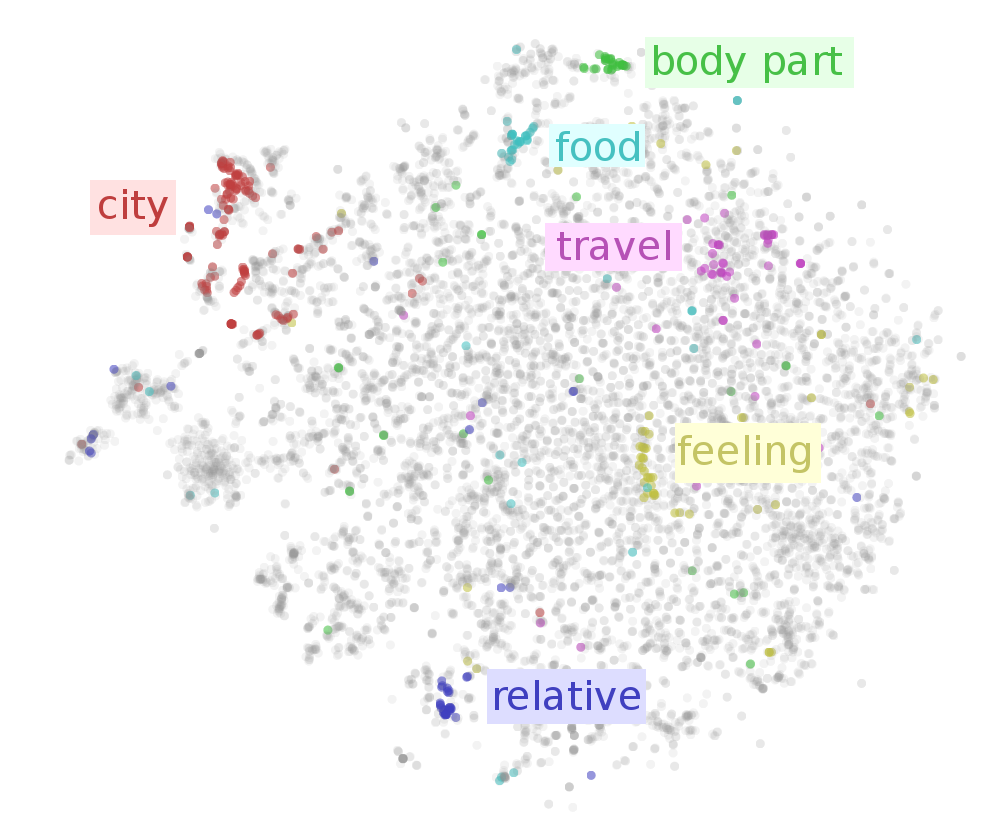

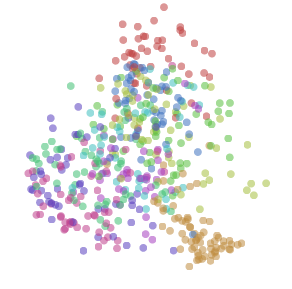

To visualize the word embedding in two dimensions, we need to choose a dimensionality reduction technique to use. t-SNE optimizes for keeping points close to their neighbors, so it is the natural tool if we want to visualize which words are close together in our word embedding.

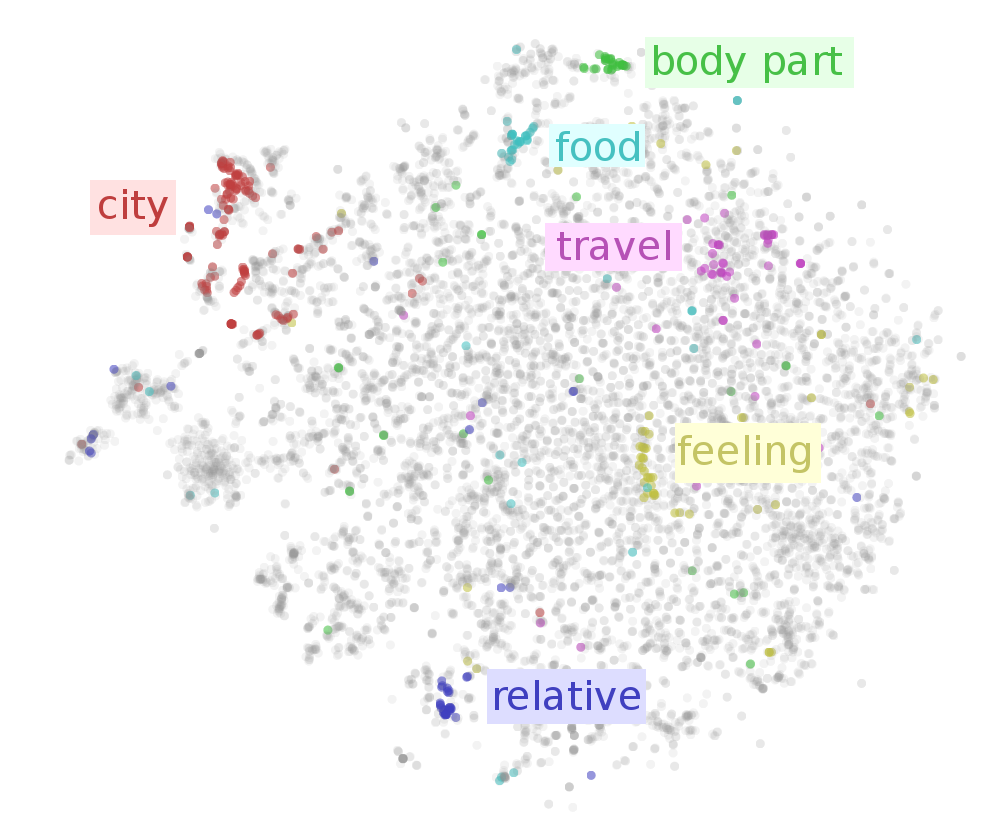

Examining the t-SNE plot, we see that neighboring words tend to be related. But there’s so many words! To get a higher-level view, lets highlight a few kinds of words.

2 We can see areas corresponding to cities, food, body parts, feelings, relatives and different “travel” verbs.

That’s just scratching the surface. In the following interactive visualization, you can choose lots of different categories to color the words by. You can also inspect points individually by hovering over them, revealing the corresponding word.

Color words by WordNetsynset (eg. region.n.03):

Looking at the above visualization, we can see lots of clusters, from broad clusters like regions (region.n.03) and people (person.n.01), to smaller ones like body parts (body_part.n.01), units of distance (linear_unit.n.01) and food (food.n.01). The network successfully learned to put similar words close together.

Example 2: Paragraph Vectors of WikipediaParagraph vectors, introduced by

Le & Mikolov (2014), are vectors that represent chunks of text. Paragraph vectors come in a few variations but the simplest one, which we are using here, is basically some really nice features on top of a

bag of words representation.

With word embeddings, we learn vectors in order to solve a language task involving the word. With paragraph vectors, we learn vectors in order to predict which words are in a paragraph.

Concretely, the neural network learns a low-dimensional approximation of word statistics for different paragraphs. In the hidden representation of this neural network, we get vectors representing each paragraph. These vectors have nice properties, in particular that similar paragraphs are close together.

Now, Google has some pretty awesome people. Andrew Dai, Quoc Le, and Greg Corrado decided to create paragraph vectors for some very interesting data sets. One of those was Wikipedia, creating a vector for every English Wikipedia article. I was lucky enough to be there at the time, and make some neat visualizations. (See

Dai, et al. (2014))

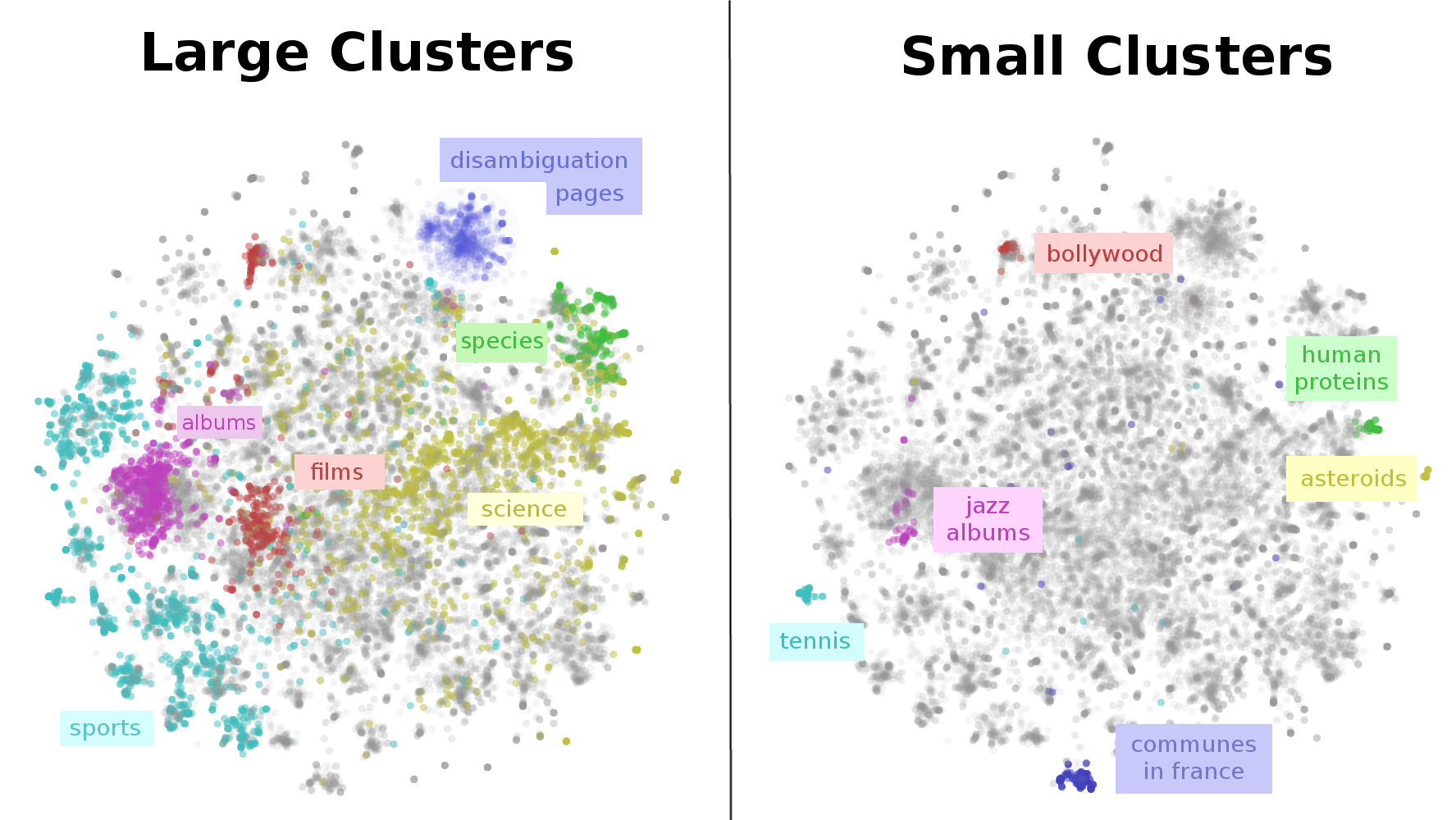

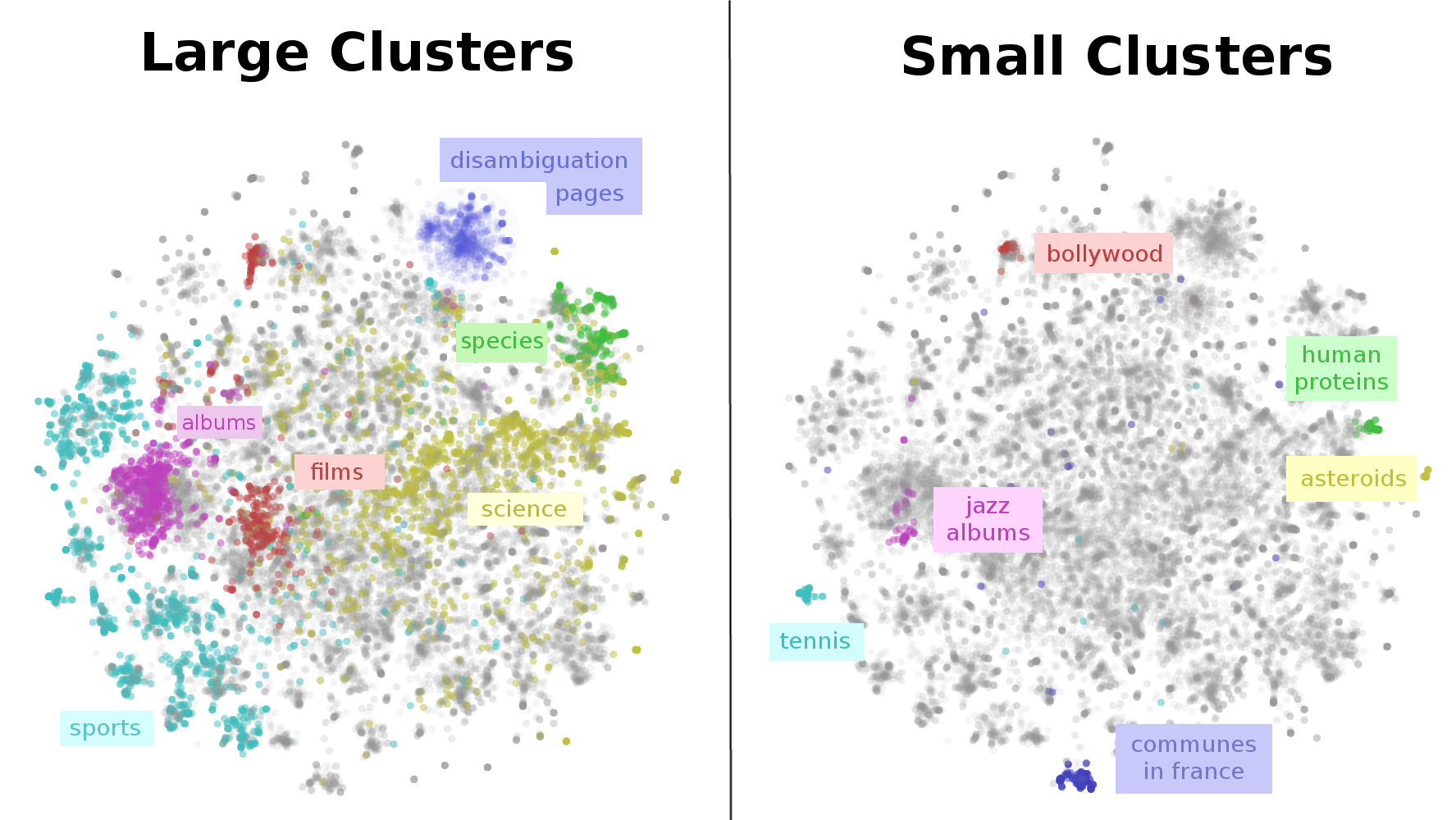

Since there are a very large number of Wikipedia articles, we visualize a random subset. Again, we use t-SNE, because we want to understand what is close together.

The result is that we get a visualization of the entirety of Wikipedia. A map of Wikipedia. A large fraction of Wikipedia’s articles fall into a few broad topics: sports, music (songs and albums), films, species, and science. I wouldn’t have guessed that! Why, for example, is sports so massive? Well, it seems like many individual athletes, teams, stadiums, seasons, tournaments and games end up with their own articles – that adds up to a lot of articles! Similar reasons lead to the large music, films and species clusters.

This map of Wikipedia presents important structure on multiple scales. While, there is a large cluster for sports, there are sub-clusters for individual sports like tennis. Films have a separate cluster for non-Western films, like bollywood. Even very fine grained topics, like human proteins, are separated out!

Again, this is only scratching the surface. In the following interactive visualization, you can explore for your self. You can color points by their Wikipedia categories, or inspect individual points by hovering to see the article title. Clicking on a point will open the article.

Color articles by Wikipedia category (eg. films):

Wikipedia Paragraph Vectors Visualized with t-SNE

(Hover over a point to see the title. Click to open article.)

(See this with 50,000 points!)

(Note: Wikipedia categories can be quite unintuitive and much broader than you expect. For example, every human is included in the category applied ethics because humans are in peoplewhich is in personhood which is in issues in ethics which is in applied ethics.)

Example 3: Translation ModelThe previous two examples have been, while fun, kind of strange. They were both produced by networks doing simple contrived tasks that we don’t actually care about, with the goal of creating nice representations. The representations they produce are really cool and useful… But they don’t do too much to validate our approach to understanding neural networks.

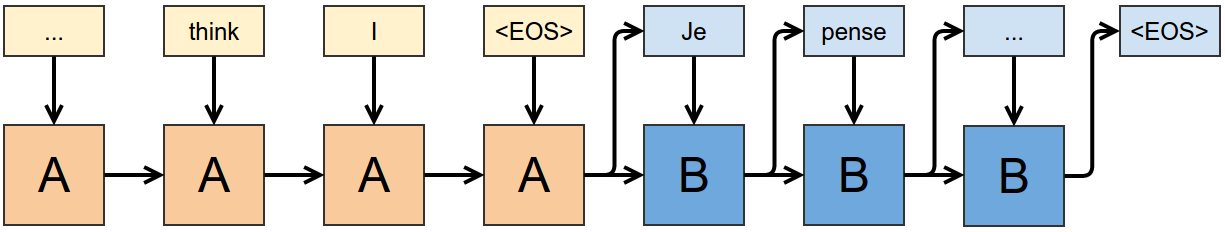

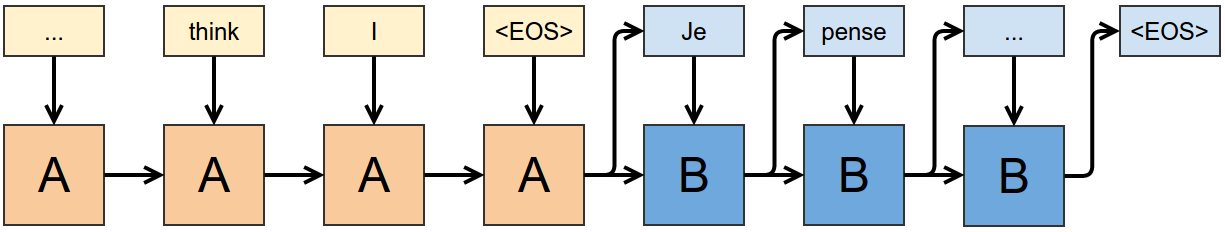

Let’s look at a cutting edge network doing a real task: translating English to French.

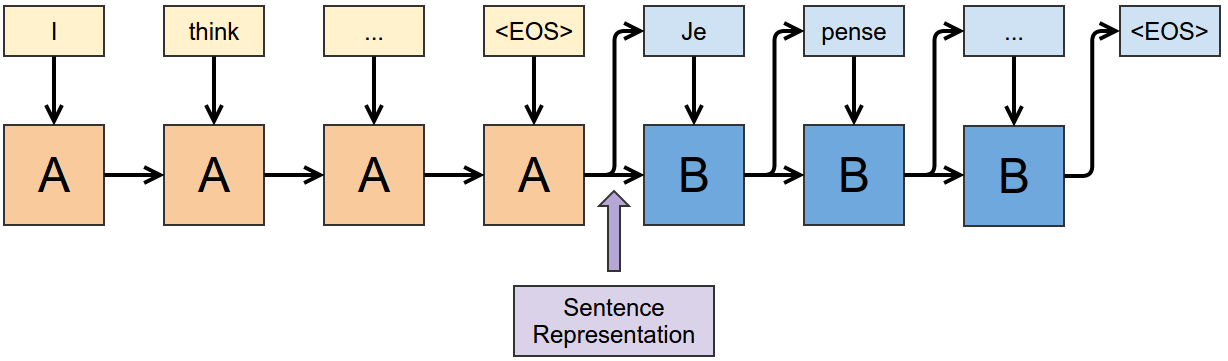

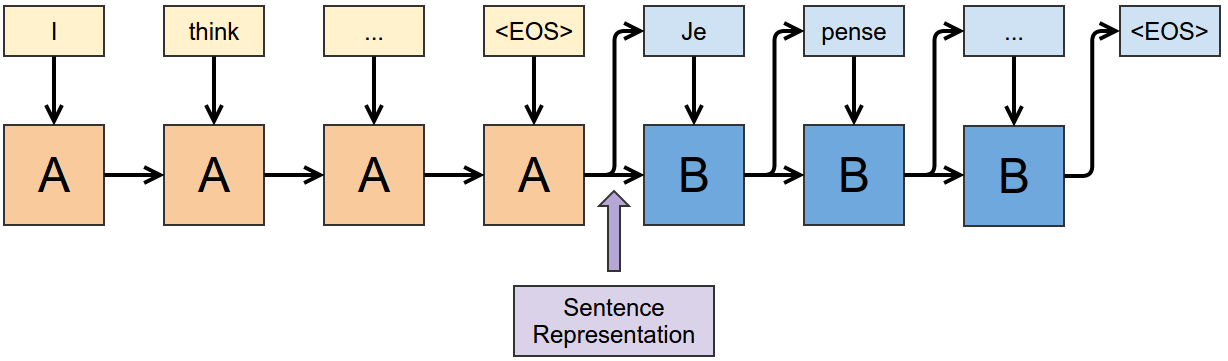

Sutskever et al. (2014) translate English sentences into French sentences using two recurrent neural networks. The first consumes the English sentence, word by word, to produce a representation of it, and the second takes the representation of the English sentence and sequentially outputs translated words. The two are jointly trained, and use a multilayered

Long Short Term Memory architecture.

3

We can look at the representation right after the English “end of sentence” (EOS) symbol to get a representation of the English sentence. This representation is actually quite a remarkable thing. Somehow, from an English sentence, we’ve formed a vector that encodes the information we need to create a French version of that sentence.

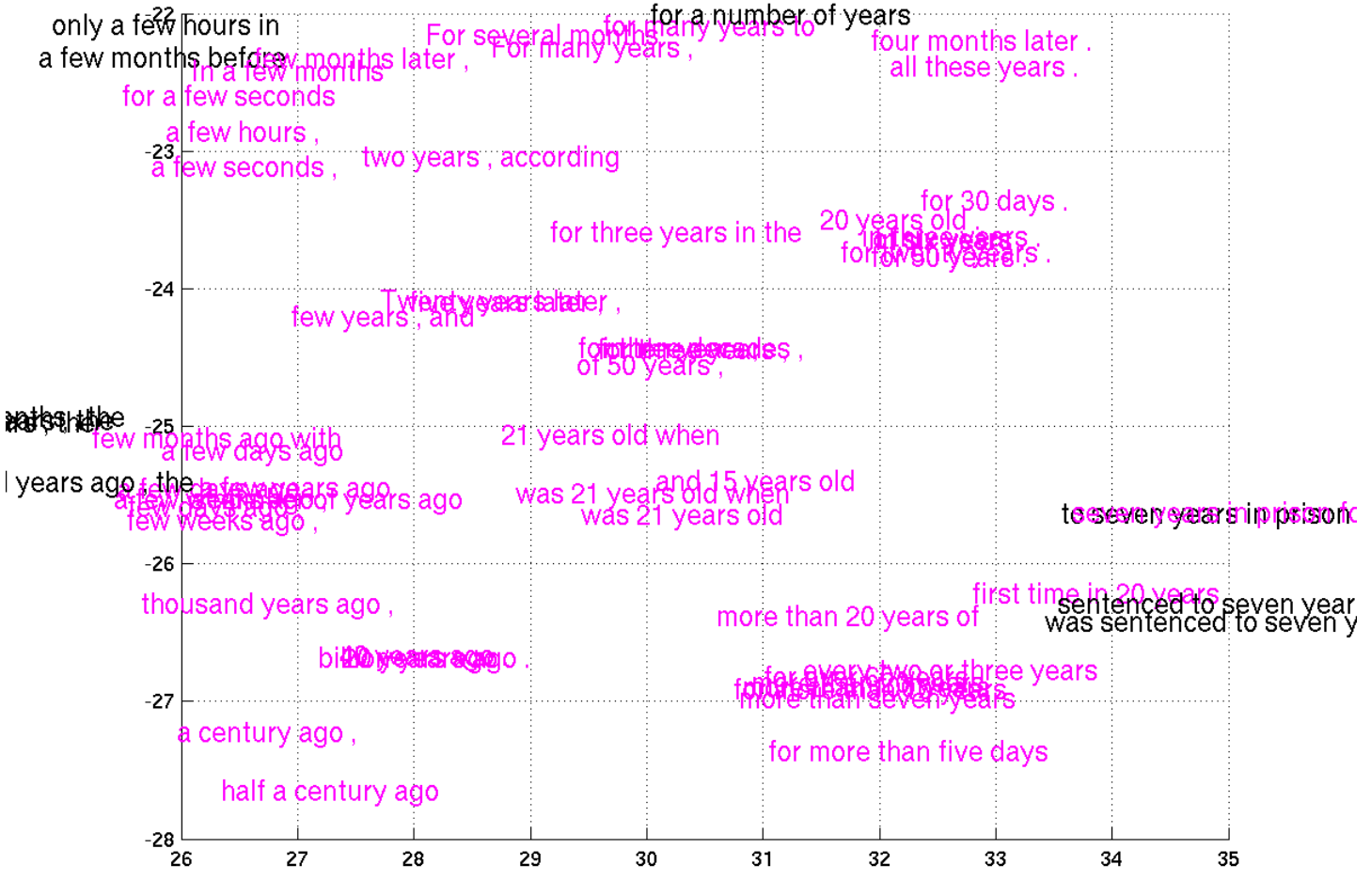

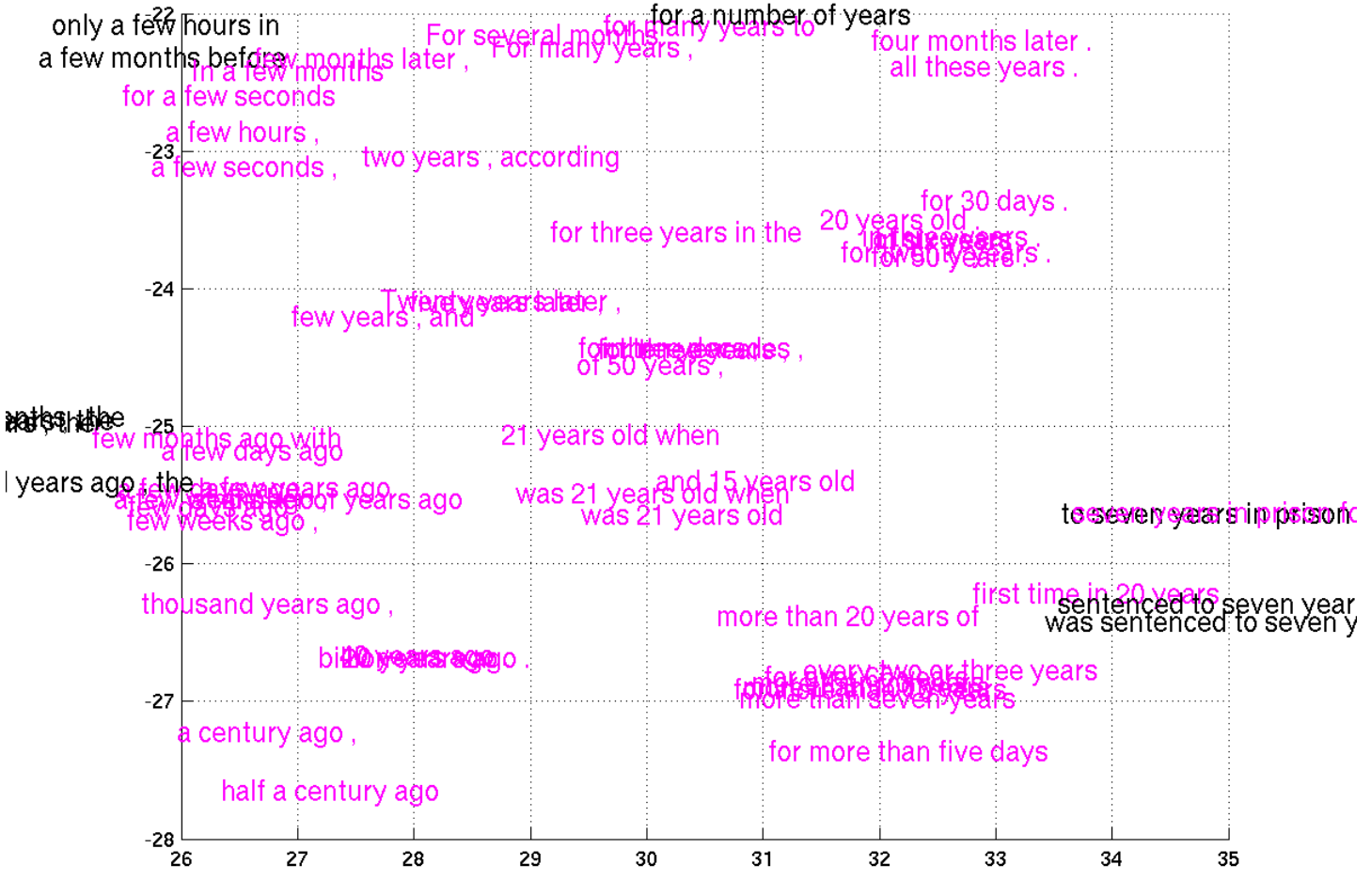

Let’s give this representation a closer look with t-SNE.

Color sentences by first word (eg. The):

Translation representation of sentences visualized with t-SNE

(Hover over a point to see the sentence.)

This visualization revealed something that was fairly surprising to us: the representation is dominated by the first word.

If you look carefully, there’s a bit more structure than just that. In some places, we can see subclusters corresponding to the second word (for example, in the quotes cluster, we see subclusters for “I” and “We”). In other places we can see sentences with similar first words mix together (eg. “This” and “That”). But by and large, the sentence representation is controlled by the first word.

There are a few reasons this might be the case. The first is that, at the point we grab this representation, the network is giving the first translated word, and so the representation may strongly emphasize the information it needs at that instant. It’s also possible that the first word is much harder than the other words to translate because, for the other words, it is allowed to know what the previous word in the translation was and can kind of Markov chain along.

Still, while there are reasons for this to be the case, it was pretty surprising. I think there must be lots of cases like this, where a quick visualization would reveal surprising insights into the models we work with. But, because visualization is inconvenient, we don’t end up seeing them.

Aside: Patterns for Visualizing High-Dimensional DataThere are a lot of established best practices for visualizing low dimensional data. Many of these are even taught in school. “Label your axes.” “Put units on the axes.” And so on. These are excellent practices for visualizing and communicating low-dimensional data.

Unfortunately, they aren’t as helpful when we visualize high-dimensional data. Label the axes of a t-SNE plot? The axes don’t really have any meaning, nor are the units very meaningful. The only really meaningful thing, in a t-SNE plot, is which points are close together.

There are also some unusual challenges when doing t-SNE plots. Consider the following t-SNE visualization of word embeddings. Look at the cluster of male names on the left hand side…

A Word Embedding Visualized with t-SNE

(This visualization is deliberately terrible.)

… but you can’t look at the cluster of male names on the left hand side. (It’s frustrating not to be able to hover, isn’t it?) While the points are in the exact same positions as in our earlier visualization, without the ability to look at which words correspond to points, this plot is essentially useless. At best, we can look at it and say that the data probably isn’t random.

The problem is that in dimensionality reduced plots of high-dimensional data, position doesn’t explain the data points. This is true even if you understand precisely what the plot you are looking at is.

Well, we can fix that. Let’s add back in the tooltip. Now, by hovering over points you can see what word the correspond to. Why don’t you look at the body part cluster?

A Word Embedding Visualized with t-SNE

(This visualization is deliberately terrible, but less than the previous one.)

You are forgiven if you didn’t have the patience to look at several hundred data points in order to find the body part cluster. And, unless you remembered where it was from before, that’s the effort one would expect it to take you.

The ability to inspect points is not sufficient. When dealing with thousands of points, one needs a way to quickly get a high-level view of the data, and then drill in on the parts that are interesting.

This brings us to my personal theory of visualizing high dimensional data (based on my whole three months of working on visualizing it):

- There must be a way to interrogate individual data points.

- There must be a way to get a high-level view of the data.

Interactive visualizations are a really easy way to get both of these properties. But they aren’t the only way. There’s a really beautiful visualization of MNIST in the original t-SNE paper,

Maaten & Hinton (2008), on the page labeled 2596:

By directly embedding every MNIST digit’s image in the visualization, Maaten and Hinton made it very easy to inspect individual points. Further, from the ‘texture’ of clusters, one can also quickly recognize their nature.

Unfortunately, that approach only works because MNIST images are small and simple. In their exciting paper on phrase representations,

Cho et al. (2014) include some very small subsections of a t-SNE visualization of phrases:

Unfortunately, embedding the phrases directly in the visualization just doesn’t work. They’re too large and clunky. Actually, I just don’t see any good way to visualize this data without using interactive media.

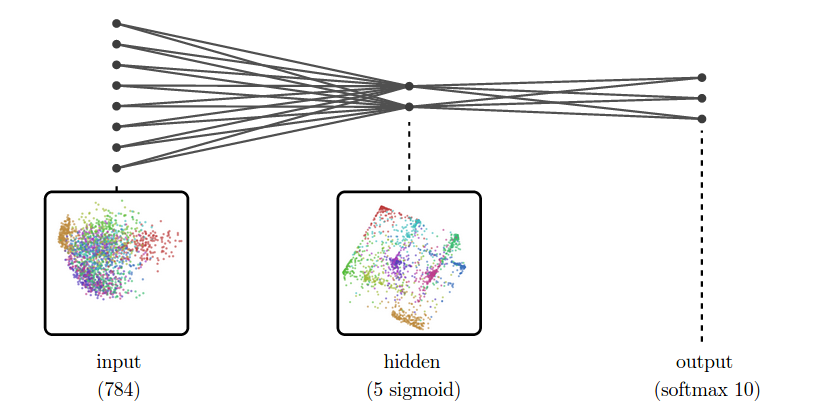

Geometric FingerprintsNow that we’ve looked at a bunch of exciting representations, let’s return to our simple MNIST networks and examine the representations they form. We’ll use PCA for dimensionality reduction now, since it will allow us to observe some interesting geometric properties of these representations, and because it is less stochastic than the other dimensionality reduction algorithms we’ve discussed.

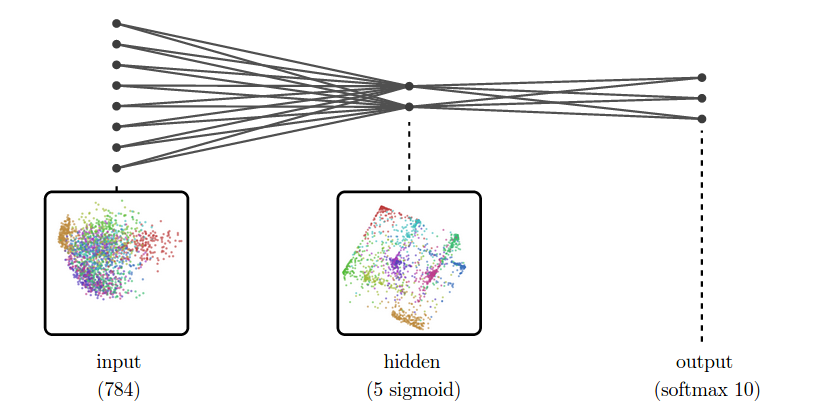

The following network has a 5 unit sigmoid layer. Such a network would never be used in practice, but is a bit fun to look at.

Then network’s hidden representation looks like a projection of a high-dimensional cube. Why? Well, sigmoid units tend to give values close to 0 or 1, and less frequently anything in the middle. If you do that in a bunch of dimensions, you end up with concentration at the corners of a high-dimensional cube and, to a lesser extent, along its edges. PCA then projects this down into two dimensions.

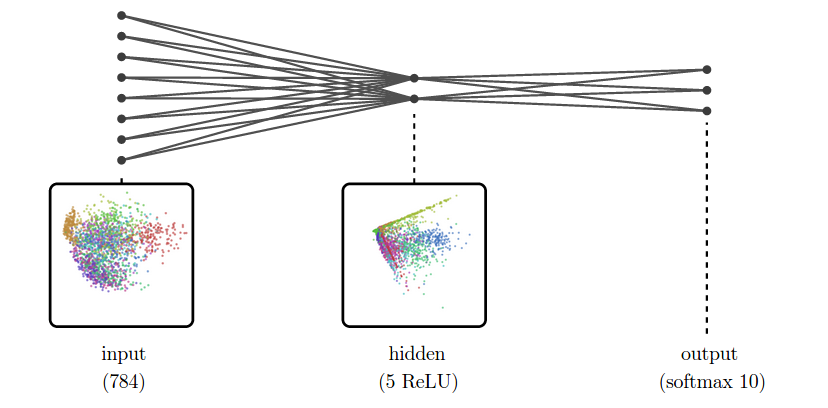

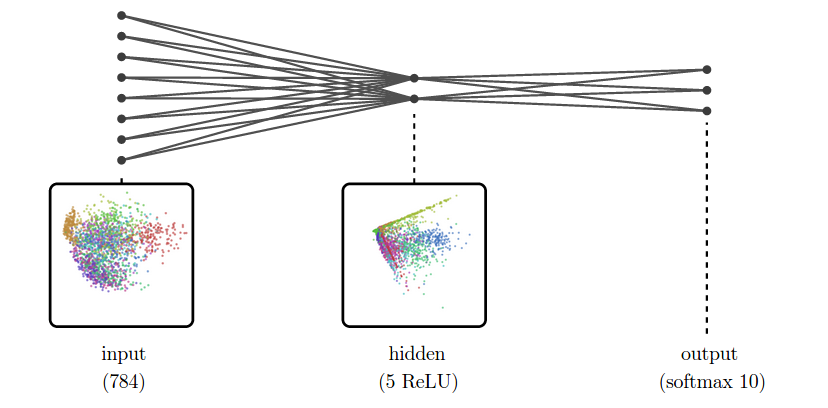

This cube-like structure is a kind of geometric fingerprint of sigmoid layers. Do other activation functions have a similar geometric fingerprint? Let’s look at a ReLU layer.

Because ReLU’s have a high probability of being zero, lots of points concentrate on the origin, and along axes. Projected into two dimensions, it looks like a bunch of “spouts” shooting out from the origin.

These geometric properties are much more visible when there are only a few neurons.

The Space of RepresentationsEvery time we train a neural net, we get new representations. This is true even if we train the same network multiple times. The result is that it is very easy to end up with lots of representations of a dataset.

We rarely look at any of these representations, but if we want to, it’s pretty easy to make visualizations of all of them. Here’s a bunch to look at.

The Many Representations of MNIST

Now, while we can visualize a lot of representations like this, it isn’t terribly helpful. What do we learn from it? Not much. We have lots of particular representations, but it’s hard to compare them or get a big picture view.

Let’s focus on comparing representations for a moment. The tricky thing about this is that fundamentally similar neural networks can be very different in ways we don’t care about. Two neurons might be switched. The representation could be rotated or flipped.

Two very similar representations, except for a flip

We want to, somehow, forget about these unimportant differences and focus only on the important differences. We want a canonical form for representations, that encodes only meaningful differences.

Distance seems fundamental, here. All of these unimportant differences are isometries – that is, transformations like rotation or switching two dimensions do not change the distances between points. On the other hand, distance between points is really important: things being close together is a representations way of saying that they are similar, and things being far apart is a representation saying they are different.

Thankfully, there’s an easy way to forget about isometries. For a representation X, there’s an associated metric function, dX, which gives us the distance between pairs of points within that representation. For another representation Y, dX=dY if and only if X is isometric to Y. The metric functions encode precisely the information we want!

We can’t really work with dX because it is actually a function on a very high-dimensional continuous space.

4 We need to discretize it for it to be useful.

DX=⎡⎣⎢⎢⎢⎢dX(x0,x0)dX(x0,x1)dX(x0,x2)...dX(x1,x0)dX(x1,x1)dX(x1,x2)...dX(x2,x0)dX(x2,x1)dX(x2,x2)...............⎤⎦⎥⎥⎥⎥

One thing we can do with DX is flatten it to get a vector encoding the properties of the representation X. We can do this for a lot of representations, and we get a collection of high-dimensional vectors.

The natural thing to do, of course, is to apply dimensionality reduction, such as t-SNE, to our representations. Geoff Hinton dubbed this use of t-SNE “meta-SNE”. But one can also use other kinds of dimensionality reduction.

5 6In the following visualization, there are three boxes. The largest one, on the left, visualizes the space of representations, with every point corresponding to a representation. The points are positioned by dimensionality reduction of the flattened distance matrices, as above. One way to think about this that distance between representations in the visualization represents how much they disagree on which points are similar and which points are different.

Next, the middle box is a regular visualization of a representation of MNIST, like the many we’ve seen previously. It displays which ever representation you hover over in left box. Finally, the right most box displays particular MNIST digits, depending on which point you hover over in the middle box.

The Space of MNIST Representations

Left: Visualization of representations with meta-SNE, points are representations. Middle:Visualization of a particular representation, points are MNIST data points. Right: Image of a particular data point.

This visualization shifts us from looking at trees to seeing the forest. It moves us from looking at representations, to looking at the space of representations. It’s a step up

the ladder of abstraction.

Imagine training a neural network and watching its representations wander through this space. You can see how your representations compare to other “landmark” representations from past experiments. If your model’s first layer representation is in the same place a really successful model’s was during training, that’s a good sign! If it’s veering off towards a cluster you know had too high learning rates, you know you should lower it. This can give us qualitative feedbackduring neural network training.

It also allows us to ask whether two models which achieve comparable results are doing similar things internally or not.

Deep Learning for VisualizationAll of the examples above visualize not only the neural network, but the data it operates on. This is because the network is inextricably tied to the data it operates on.

7The visualizations are a bit like looking through a telescope. Just like a telescope transforms the sky into something we can see, the neural network transforms the data into a more accessible form. One learns about the telescope by observing how it magnifies the night sky, but the really remarkable thing is what one learns about the stars. Similarly, visualizing representations teaches us about neural networks, but it teaches us just as much, perhaps more, about the data itself.

(If the telescope is doing a good job, it fades from the consciousness of the person looking through it. But if there’s a scratch on one of the telescope’s lenses, the scratch is highly visible. If one has an example of a better telescope, the flaws in the worse one will suddenly stand out. Similarly, most of what we learn about neural networks from representations is in unexpected behavior, or by comparing representations.)

Understanding data and understanding models that work on that data are intimately linked. In fact, I think that understanding your model has to imply understanding the data it works on.

8While the idea that we should try to visualize neural networks has existed in our community for a while, this converse idea – that we can use neural networks for visualization – seems equally important is almost entirely unexplored.

Let’s explore it.

Unthinkable Thoughts, Incomprehensible DataIn his talk ‘Media for Thinking the Unthinkable’, Bret Victor raises a really beautiful quote from Richard Hamming:

Just as there are odors that dogs can smell and we cannot, as well as sounds that dogs can hear and we cannot, so too there are wavelengths of light we cannot see and flavors we cannot taste.

Why then, given our brains wired the way they are, does the remark “Perhaps there are thoughts we cannot think,” surprise you?

Evolution, so far, may possibly have blocked us from being able to think in some directions; there could be unthinkable thoughts.

Victor continues with his own thoughts:

These sounds that we can’t hear, this light that we can’t see, how do we even know about these things in the first place? Well, we built tools. We built tools that adapt these things that are outside of our senses, to our human bodies, our human senses.

We can’t hear ultrasonic sound, but you hook a microphone up to an oscilloscope and there it is. You’re seeing that sound with your plain old monkey eyes. We can’t see cells and we can’t see galaxies, but we build microscopes and telescopes and these tools adapt the world to our human bodies, to our human senses.

When Hamming says there could be unthinkable thoughts, we have to take that as “Yes, but we build tools that adapt these unthinkable thoughts to the way that our minds work and allow us to think these thoughts that were previously unthinkable.”

This quote really resonates with me. As a machine learning researcher, my job is basically to struggle with data that is incomprehensible – literally impossible for the human mind to comprehend – and try to build tools to think about it and work with it.

9However, from the representation perspective, there’s a further natural step to go with this idea…

Representations in Human VisionLets consider human vision for a moment. Our ability to see is amazing. The amazing part isn’t our eyes detecting photons, though. That’s the easy, simple part. The amazing thing is the ability of our brain to transform the mess of swirling high-dimensional data into something we can understand. To present it to us so well that it seems simple! We can do this because our brains have highly specialized pathways for processing visual data.

Just as neural networks transform data from the original raw representations into nice representations, the brain transforms our senses from complicated high-dimensional data into nice representations, from the incomprehensible to the comprehensible. My eye detects photons, but before I even become consciously aware of what my eye sees, the data goes through incredibly sophisticated transformations, turning it into something I can reason about.

10 The brain does such a good job that vision seems easy! It’s only when you try to understand visual data without using your visual system that you realize how incredibly complicated and difficult to understand it is.

Unfortunately, for every sense we have, there are countless others we don’t. Countless modes of experience lost to us. This is a tragedy. Imagine the senses we could have! There are vast collections of text out there: libraries, wikipedia, the Internet as a whole – imagine having a sense that allowed you to see a whole corpus at once, which parts are similar and which are different! Every collision at the Large Hadron Collider is monitored by a battery of different sensors – imagine having a sense that allowed us to ‘see’ collisions as clearly as we can see images! The barrier between us and these potential senses isn’t getting the data, it’s getting the data to our brain in a nice representation.

The easiest way get new kinds of data into the brain is to simply project it into existing senses. In some very particular cases, this works really well. For example, microscopes and telescopes are extremely good at making a new kind of data accessible by projecting it into our normal visual sense. They work because macroscopic visual data and microscopic visual data are just visual data on different scales, with very similar structure to normal visual data, and are well handled by the same visual processing systems. Much more often, projecting data into an existing sense (for example, with PCA) throws away all but the crudest facets of the data. It’s like taking an image and throwing away everything except the average color. It’s something… but not much.

We can also try to get this data to us symbolically. Of course, rattling off 10,000-dimensional vectors to people is hopeless. But traditional statistics gives us some simple models we can fit, and then discuss using language of means, variance, covariance and so on. Unfortunately, fitting gaussians is like describing clouds as ovals. Talking about the covariance of two variables is like talking about the slope, in a particular direction, of a high-dimensional surface. Even very sophisticated models from statistics seem unable to cope with the complicated, swirling, high-dimensional data we see in problems like vision.

Deep learning gives us models that can work with this data. More that that, it gives us new representations of the data. The representations it produces aren’t optimized to be nice representations for the human brain – I have no idea how one would optimize for that, or even what it would mean – but they are much nicer than the original data. I think that learning representations, with deep learning or other powerful models, is essential to helping humans understand new forms of data.

A Map of WikipediaThe best example I can give is the visualization of Wikipedia from earlier. Wikipedia is a repository of human knowledge. By combining deep learning and dimensionality reduction, we can make a map of it, as we saw earlier:

Map of Wikipedia

(paragraph vectors and t-SNE – see Example 2 above)

This style of visualization feels important to me. Using deep learning, we’ve made a visualization, an interface, for humans to interact with Wikipedia as a whole. I’m not claiming that it’s a great interface. I’m not even sure I think it is terribly useful. But it’s a starting point and a proof of concept.

Why not just use dimensionality reduction by itself? If we had just used dimensionality reduction, we would be visualizing geometric or topological features of the Wikipedia data. Using deep learning to transform the data allows us to visualize the underlying structure, the important variations – in some cases, the very

meaning of the data

11 – instead.

I think that high-quality representations have a lot of potential for users interacting with complicated data, going far beyond what is explored here. The most natural direction is machine learning: once you are in a high-quality representation, many normally difficult tasks can be accomplished with very simple techniques and comparatively little data.

12 With a curated collection of representations, one could make some really exciting machine learning accessible,

13although it would carry with it challenges for end users

14 and the producers of representations.

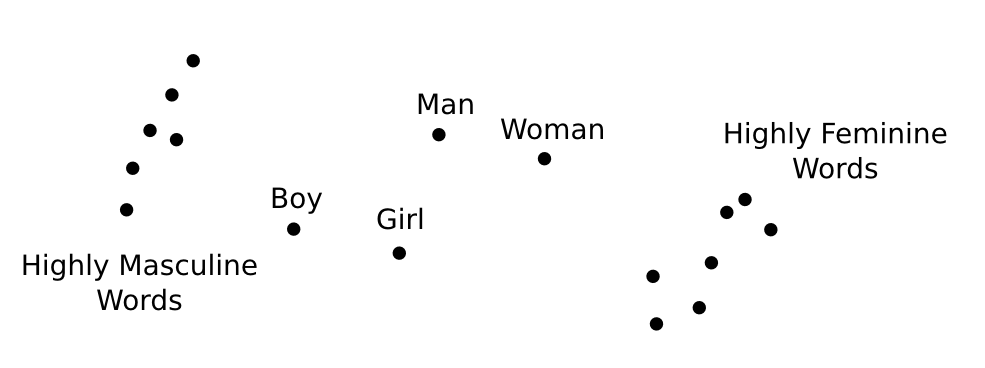

15Reasoning about data through representations can be useful even for kinds of data the human mind understands really well, because it can make explicit and quantifiable things that are normally tacit and subjective.

You probably understand English very well, but much of this knowledge is subjective. The meaning of words is socially constructed, arising from what people mean by them and how they use them. It’s canonicalized in dictionaries, but only to a limited extent. But the subtleties in usage and meaning are very interesting because of how they reflect culture and society. Unfortunately, these things are kind of fuzzy, and one typically needs to rely on anecdotes and personal impressions.

One remarkable property of high-quality word embeddings is that they seem to reify these fuzzy properties into concrete mathematical structures! As mentioned earlier, directions in word embeddings correspond to particular kinds of differences in meaning. For example, there is some direction corresponding to gender. (For more details, see my post

Deep Learning, NLP, and Representations.)

By taking the difference of two word vectors, we can get directions for gender. For example, we can get a masculine direction (eg. “man” - “woman”) or a feminine direction (eg. “woman” - “man”). We can also get age directions. For example, we can get an adult direction (eg. “woman” - “girl”) or a child direction (eg. “boy” - “man”).

Once we have these directions, there’s a very natural question to ask: which words are furthest in these directions? What are the most masculine or feminine words? The most adult, the most childish? Well, let’s look at the Wikipedia

GloVe vectors, from Pennington,

et al. at Stanford:

- Masculine words tend to be related to military/extremism (eg. aresenal, tactical, al qaeda), leadership (eg. boss, manager), and sports (eg. game, midfielder).

- Female words tend to be related to reproduction (eg. pregnancy, birth), romance (eg. couples, marriages), healthcare (eg. nurse, patients), and entertainment (eg. actress).

- Adult words tend to be related to power (eg. victory, win), importance (eg. decisive, formidable), politics (eg. political, senate) and tradition (eg. roots, churches).

- Childish words tend to be related to young families (eg. adoption, infant), activities (eg. choir, scouts), items (eg. songs, guitar, comics) and sometimes inheritance (eg. heir, throne).

Of course, these results depend on a lot of details.

16I’d like to emphasize that which words are feminine or masculine, young or adult, isn’t intrinsic. It’s a reflection of our culture, through our use of language in a cultural artifact. What this might say about our culture is beyond the scope of this essay. My hope is that this trick, and machine learning more broadly, might be a useful tool in sociology, and especially subjects like gender, race, and disability studies.

The FutureRight now machine learning research is mostly about getting computers to be able to understand data that humans do: images, sounds, text, and so on. But the focus is going to shift to getting computers to understand things that humans don’t. We can either figure out how to use this as a bridge to allow humans to understand these things, or we can surrender entire modalities – as rich, perhaps more rich, than vision or sound – to be the sole domain of computers. I think user interface could be the difference between powerful machine learning tools – artificial intelligence – being a black box or a cognitive tool that extends the human mind.

There’s actually two kinds of black boxes we need to avoid. Two slightly different, but closely connected problems. The first problem is that deep learning itself is presently a kind of black box. The second is that tools using deep learning to solve particular problems might be black boxes.

We need to figure out how to open the deep learning black box. One powerful approach is visualizing representations. In this essay, we used interactive media to visualize and explore some powerful models from Google’s deep learning research group. We then observed that particular neural network architectures leave geometric signatures in their representations. Finally, we created the meta-SNE algorithm, in order to step up the ladder of abstraction, and think about the space of neural networks, instead of particular ones.

The problem of particular tools being black boxes is, in some ways, harder, because there’s so much diversity. But a common problem is that humans can’t think about the sort of high-dimensional structures machine learning problems typically involve. We observed that visualizing representations can also be a tool to help humans understand and reason about these structures. We saw that representations can be helpful even for data we understand really well.

These are problems we’re only beginning to attack. I think there’s a lot more for us to uncover here. It’s an odd kind of work, at the intersection of machine learning, mathematics, and user interface. But I think it’s important.

If you enjoyed this post, consider subscribing to my

rss feed.

(I would be delighted to hear your comments and thoughts: you can comment inline or at the end. For typos, technical errors, or clarifications you would like to see added, you are encouraged to make a pull request on github.) AcknowledgementsI’m grateful for the hospitality of Google’s deep learning research group, which had me as an intern while I did most of the work this post is based on. I’m especially grateful to my internship host,

Jeff Dean.

I was greatly helped by the comments, advice, and encouragement of many Googlers, both in the deep learning group and outside of it. These include:

Greg Corrado,

Jon Shlens, Matthieu Devin, Andrew Dai,

Quoc Le, Anelia Angelova,

Oriol Vinyals,

Ilya Sutskever,

Ian Goodfellow, Jutta Degener, and Anna Goldie.

I was strongly influenced by the thoughts, comments and notes of

Michael Nielsen, especially

his notes on

Bret Victor’s work. Michael’s thoughts persuaded me that I should think seriously about interactive visualizations for understanding deep learning. The section “Unthinkable Thoughts, Incomprehensible Data” was particularily influenced by him.

This blog post was made possible by a number of wonderful Javascript libraries, including

D3.js,

MathJax, and

jQuery. A big thank you to everyone who contributed to these libraries.

The representation perspective is an abstraction over inputs. Instead of trying to understand what the neural network does to a single input, we try to understand what it does to the space of inputs, to the data manifold. It’s a step up

the ladder of abstraction. Later, we will take a second step, allowing us to look at the space of neural networks, instead of a single one.

↩We categorize words using WordNet synsets. Each synset is labeled something like “region.n.03” (region, noun, meaning 3) or “travel.v.01” (travel, verb, meaning 1).

↩It should be noted that, later, Sutskever

et al. switched to reversing the order of the input sentence, finding this improved their results.

↩

↩The natural way to think about distance between functions is to consider them as infinite dimensional vectors (f(0), f(1), f(2)...). In the case of a function on the real numbers or on Rn, it’s a 2ℵ0 dimensional vector! While we can actually represent the function finitely (because we know it’s based on a neural network, which has a finite number of paramaters) it’s really hard to actually calculuate disances.

↩I’ve heard that some similar techniques may be used in neuroscience, where one often needs to compare different representations of the same data. Further, in a previous post, John MacCuish commented that one could use the Mantel Test on the distance matrices to compare representations – this gets at a very similar idea!

↩There are some variations you can do on the basic meta-SNE algorithm. For example, meta-SNE analyzes how much representations agree on which data points are similar, by comparing distance between the points in different representations. But we can also compare how much representations agree on analogies, on the manner in which things are different, by comparing the distance between differences of vectors in different representations. In principle, this information is encoded in the distances between data points, but one can make it much more explicit. It may also be the case that we care more about which networks are very similar, in which case we could apply some non-linearity pointwise to the distance matrix, to exaggerate the difference between close and not-close data points.

↩The neural network is a function with the domain of the data manifold it was trained on.

↩People sometimes complain: “Neural networks are so hard to understand! Why can’t we use understandable models, like SVMs?” Well, you understand SVMs, and you don’t understand visual pattern recognition. If SVMs could solve visual pattern recognition, you would understand it. Therefore, SVMs are not capable of this, nor is any other model you can really understand. (I don’t mean this to be a ‘proof’ obviously, but I am pretty serious about this view.)

↩You could imagine defining a field this way, as attempting to build tools for thinking about and working with the complicated high-dimensional probability distributions we see in the real world. The field you get ins’t quite machine learning, but it has a lot of overlap. It actually feels more compelling to me. Perhaps this is “data science”?

↩As someone without a neuroscience background, I feel a bit nervous making remarks like this. That said, I think what I’m mostly saying is an interpretation, an abstraction, over some fairly basic facts about how human vision works. I also know that at least some neuroscientists subscribe to this interpretation and seriously look at things through this sort of lens. For example, see

DiCarlo and Cox’s paper ‘Untangling invariant object recognition’.

↩This is a very bold claim. My defense is this: word embedding models seem to encode semantic meaning in directions, creating a “semantic vector space.” Paragraph vectors (at least the kind that we’re using) do the same. Somehow, these models seem to discover human meaning while learning the structure of the space. The results of the DeViSE paper suggest that this may be somewhat general in good high-level representations.

↩This is some combination of transfer learning, pretraining, and multi-task learning. How well it works varies, but there’s certainly a lot of successes. Obviously, the ideal is to have a lot of data to train a representation specifically for your task, but failing that. We can also try to make very transferable representations, possibly by training them for a bunch of different tasks.

↩Curating large collections of structured data has lead to some really interesting tools (for example, Wolfram Alpha). My intuition is that curating a collection of high-quality representations for different kinds of data could also be really interesting. I think

MetaMindis the closest thing I know of to this, right now.

↩It seems like a lot of the problems that exist with proprietary file formats could end up happening here. An end user could very easily end up tied to a particular representation. Do we need open or standardized representations?

↩The problem with just releasing representations, from the perspective of the model producer, is what Geoff Hinton calls “Dark Knowledge”. Representations subtly encode a lot of the knowledge of your model. By releasing representations, organizations are implicitly releasing a significant amount of information about their model.

↩The answer depends a lot on the corpus you train on. If you train your word embedding on a news corpus, that will be different than if you train it on Wikipedia. And I assume if you trained on a corpus of 19th century literature, that would be very different again. It also depends on your model, and how well you trained it. The precise interpretation is obviously sensitive to the model. But, generally, it will be something like this: There is a certain difference in how language is used around the word “man” and the word “woman”; which words cause language around them to change most in that manner? (Replace “man” and “woman” for whatever you want.)

发表于 2015-3-16 01:49:34

发表于 2015-3-16 01:49:34